City Fragment: Vertical Botanic Garden

The Packard Plant is an elemental work of architecture. Albert Kahn’s Packard Number Ten, completed in 1905, was the first automobile factory to be constructed in reinforced concrete. The Packard Plant is not so much a building as a serial assemblage of parts—columns, slabs, windows, roof. It is the archetypal 20th century space of production. Today it exists as a ruin, preserved almost accidentally, in part due to the strength of its reinforced concrete construction.

Any proposal to repurpose the Packard Plant must come to terms with the hard realities of contemporary Detroit. At one time a dynamic city driven by the prosperity of the automobile industry, today Detroit is scarred by decline. The urban and social landscape has been emptied out by poverty and neglect, and the economic base is fragile. The positive signs of renewal do not scale to the Packard Plant. The site is too remote, the scale too vast and the urban fabric too fragmented. In short the usual urban design strategies will not work here. On the other hand, the assets of the site are extraordinary, beginning with the quality and scale of the architecture itself. This is a radical architecture based on endless repetition and vast horizontal spaces.

Refusing the seduction of the post-industrial ruin, our project looks for opportunities in the elemental character of the architecture itself: a platform for new programs, and new futures for Detroit. The project operates at four interrelated levels: urban; infrastructural; architectural and programmatic. This separation into levels is provisional only, and the parts—like the city itself—form a larger, ‘difficult’ whole. Above all, our approach is fundamentally architectural: these four levels represent four essential dimensions of the architect’s imagination.

A Situation Constructed from Loose and Overlapping Social and Architectural Aggregates

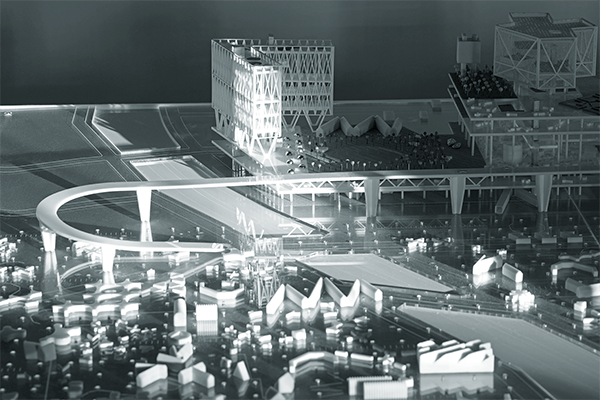

The MOS proposal works with and within the overlapping and disaggregated connections between urban and social form. Situated above and around the Dequindre Cut, it uses a low-rise high-density development – produced through the loose arrangement of empty types, frameworks, and open spaces – to connect existing conditions with a new urban fabric. At grade, a neighborhood of common spaces links the community with the Cut and the existing street system. The structure and circulation are based on the economical model of highway and parking structures. A series of spiral ramps punctuate the structure, connecting all levels with pedestrian and vehicular traffic. A perennial garden and plaza extend across the roof, creating a network of spaces for recreation and social gathering. Thin buildings maximize the surface area of their facades, and in turn maximize daylighting. The emptied typologies serve as an open framework for something else, imagined by someone else, to happen. They are owned collectively, they do not front streets, and they work outside conventional notions of property and lots. The thresholds between interior and exterior – roofs, ramps, porches, and overhangs – provide informal areas for neighbors to commune. Every exterior space is a public space; every interior space is a public space.